- Home

- Laurie Hess

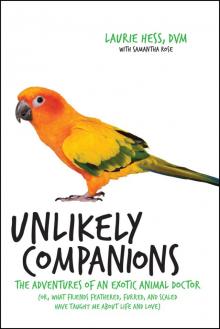

Unlikely Companions

Unlikely Companions Read online

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Da Capo Press was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters.

Copyright © 2016 by Laurie Hess

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 53 State Street, 9th floor, Boston, MA 02109.

Designed by Linda Mark

Set in 12.25 point Weiss Std by the Perseus Books Group

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hess, Laurie, author.

Title: Unlikely companions: the adventures of an exotic animal veterinarian (or, what friends feathered, furred, and scaled have taught me about life and love) / Dr. Laurie Hess, DVM, Diplomate AVBP (Avian) Exotic Animal Veterinarian, with Samantha Rose.

Description: First Da Capo Press edition. | Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016024797 (print) | LCCN 2016035439 (ebook) (print) | LCCN 2016035440 (ebook) | ISBN 9780738219585 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Exotic animals—Diseases—Anecdotes. | Pet medicine—Anecdotes. | Hess, Laurie.

Classification: LCC SF997.5.E95 H47 2016b (print) | LCC SF997.5.E95 (ebook) | DDC 636.089—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016024797

First Da Capo Press edition 2016

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

www.dacapopress.com

The names and identifying details of people associated with events described in this book have been changed. Any similarity to actual persons is coincidental.

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA, 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail [email protected].

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

E3-20170401-JV-PC

NOTE TO READERS

This story is based on real events. Except for the names of Dr. Hess’ family members, the names and some identifying characteristics of the other people and companies mentioned in this book have been changed.

To all the birds and exotic animals

and the owners who love and care for them.

CONTENTS

1A Mysterious Case

2Will I Ever Belong?

3A Connection

4Meet Me in the Middle

5Unraveling

6Piece by Piece

7Love Without Reservation

Exotic Pet Resources

About the Authors

Acknowledgments

1

A MYSTERIOUS CASE

MONDAY, 4:28 A.M., HOME

I got the call in what felt like the middle of the night.

“He’s dead, Laurie,” said my head technician, Marnie.

I threw back the quilt and scurried out of bed and down the hallway, cell phone in hand. I was careful not to wake my husband, Peter, who had gotten into bed only a few hours before, back from a long week of providing legal counsel on the other side of the country.

The uneven floor creaked in our center-hall colonial. Through the narrow four-paned window at the top of the stairs, I could barely make out the tangle of naked maple trees in our almost pitch-black backyard.

My cell phone confirmed that it was early: 4:28 a.m. As a local vet, I keep the same hours as many of the farmers in my community do. At five o’clock every morning, the reassuring aroma of espresso roast makes its way upstairs, but at this hour, the kitchen was still and quiet.

“I found him in his incubator this morning,” Marnie said. “And I just received a call from Bob Dixon. He wants to bring in Lily. The symptoms are the same, and I fear the worst. How quickly can you be at the hospital?”

This was the fourth death in less than ten days, and, like Marnie, I’d been holding my breath, worried that there might be more. Now she’d confirmed that we’d lost another, and Lily was sick. I wouldn’t have time to wait for my first cup of coffee.

“I’m on my way.”

I hurried to get dressed, pulling on workout clothes over my insulin pump, then my knee-high leather Frye boots and Marmot down jacket, the winter uniform of country and not-so-country vets far and wide. A quick check of my blood sugar—I have type 1 diabetes—told me that I had to eat before rushing off, so, accompanied by my four cats, Bingo, Gizmo, Tilly, and Bean, who thought I’d gotten up to feed them, I tiptoed on the wide-planked pine floors through our dark farmhouse and into the kitchen, nearly falling over a mountain of bags. I’m constantly on my middle school sons, Brett and Luke, for creating an obstacle course of boyhood gear wherever they go, but this time the mess was my own—pelleted bird food that I myself had brought home for our pionus parrot, Dale. So I really couldn’t complain. Our house had been named “Applewood” when it was originally built as the groomsman’s house on an estate; now we simply called it the “Hess-Mess.”

Because Peter had been out of town, the fridge was emptier than usual, as he’s our main provisioner. I settled for a string cheese in one pocket and an apple in the other and scampered out the door, down the flagstone path to the driveway. The sun was not yet rising, and it would be several hours before the ground thawed. Winter temperatures had dropped below twenty degrees overnight, and a thin sheet of ice covered my Highlander windshield, a good indicator that the air was frigid. With mittened hands clutching the ice scraper, I removed the ice from the windows quickly but with surgical precision. The hospital is only seven minutes from home, so, if I hurried, I might make it back before the school bus arrived. It was Monday morning, and with Peter still on West Coast time, I regretted leaving him to rouse the boys single-handedly and get them out the door.

I found Marnie in the intensive care unit of the animal hospital wearing her scrubs and carefully tagging the body.

“Good morning,” I whispered as I slipped in. I didn’t want to startle her, but I did.

She turned quickly and said, “That was fast. You’re already here.”

I extended a coffee from Starbucks, which—thankfully for us—opens its doors at 5 a.m. She gave me a tired smile and took the oversized cup from my hands. I was grateful to Marnie for staying overnight at the hospital. When she offered, I’d initially declined, because overnights were not standard practice. But given the seriousness of the case and the need for round-the-clock supportive care, I’d finally decided it was a good idea.

“Peter’s back from Los Angeles now, so I can take over.”

She looked down at the body. “I was sure he was going to make it, but he stopped responding to the antibiotics early this morning.” Her voice trailed off. Marnie doesn’t give in to emotion easily, but she was taking this especially hard. Of course she cares about all of our patients, as I do, and sometimes you make an especially strong connection with certain animals. Georgie had been one of them.

“It’s not your fault, Marnie. We both tried everything.”

I walked over to the exam table where she’d laid the five-inch body out on a clean white towel. I reached down and stroked Georgie’s velvety fur. With his doe-shaped eyes closed and long puffy tail wrapped around him, the sugar glider looked as if he were simply cuddled up for a warm winter’

s nap. I ran a finger down the black stripe on Georgie’s back and imagined the little marsupial sailing through the air, wide-eyed and gleeful as he jumped from branch to branch in his milder native Australian habitat. The fold, or flap, of skin that stretches from their front toes to their ankles enables these unique animals to sail through the air. I thought of him catching the breeze, as light as a kite in the wind.

But now Georgie lay there looking both extinguished and newborn at the same time. I remembered how as babies, Brett and Luke had slept peacefully in their hospital bassinettes in those first few hours of life, with Peter and me peering down on them with that delight and wonder that all new parents must feel. I thought about Georgie’s own mother. How had she looked at him on that first night of his arrival, as he lay snuggled in her pouch?

Georgie was a doll, a bright and playful little creature. And though I’d treated many sugar gliders in recent years, none had been quite as young and slight as Georgie. He was just over a month out of pouch and could fit into the palm of a child’s hand.

“I really hoped he’d be the one to bounce back, too,” I said, smiling wearily at Marnie. “When I left the hospital last night, I thought, maybe tomorrow’s the day he makes a sudden recovery and leaps into my arms. But he was just so young and vulnerable. Like the others, he got too weak, too fast, to recover.”

“Would you like me to phone Maxine?” Marnie asked.

When an animal dies at the hospital without its owner present, we must make what is always a difficult call. First, we have to deliver the news that no pet owner wants to hear, and then we need to discuss what the owner wants us to do with the body. Many owners want to bury their own pets; others ask us to cremate them. As we comply with their wishes, we also collect something from their pet—a lock of hair, a few feathers, or a footprint—that we pass along in a sympathy card. I noticed now that an impression of Georgie’s tiny webbed toes was already on a card taped to the back counter of the ICU, the ink imprint smaller than my thumbnail. Marnie’s signature was the first on it.

As the head tech of the hospital, Marnie often has the responsibility of being the first line of communication with clients, but considering the overnight hours she’d just logged and the nature of the message, I offered to call Georgie’s owner. Then I said, “Why don’t you take a break while you can.”

I took a deep breath. Georgie’s death was only the first order of business today. I had appointments booked solid: an umbrella cockatoo, a chinchilla, a blue-tongued skink, a pregnant potbellied pig, and a ferret possibly needing surgery. I often jest that while an exotic pet hospital is very different from a zoo, on Monday mornings it sure can feel like one.

As I have with my own home, I’ve created this menagerie of managed chaos; so again, I have no one to blame but myself. As far as I know, I’m the only exotic pet veterinarian in the tristate area who offers emergency phone consultations—at midnight, on weekends, or even, as my kids like to remind me, when we’re walking through the Magic Kingdom on vacation.

My phone starts to buzz as soon as I close the hospital doors late Saturday afternoon with calls from frantic pet owners asserting “health emergencies.” Most of the time, the descriptions sound perfectly benign, so I’ll say something like, “I understand your concern. Right now, this doesn’t sound quite like an emergency, but if you’re still really concerned, I can send you to the emergency hospital for an evaluation by the on-duty veterinarian. Otherwise, I suggest you monitor your pet over the weekend, and on Monday morning, call me back.” Most of the time, I don’t get a call back. A crowd of exotic pet owners shows up in the hospital lobby instead. A week ago on Monday, I walked through the door at a quarter to nine and was greeted by a spiny hedgehog with gastrointestinal issues that his eleven-year-old owner insisted could not wait another minute. “He’s got really bad farts,” the boy said, making a stink face. “Please make it stop.”

This morning I expected to find the owner of an orange-and-white Creamsicle-looking corn snake in the waiting room as soon as the clock struck nine. I’d received her insistent call Saturday night just after I’d said goodnight to the boys and was heading downstairs to pour myself a glass of my favorite New Zealand sauvignon blanc, flip on the evening news, and start combing through veterinary journals online. Never a down moment, I thought to myself, but because I understand that finding a vet after hours for a Labrador retriever or a tabby cat is hard enough, I always answer the call.

“Hello, this is Dr. Hess,” I said, running a hand through my dark, curly hair. My hair is difficult to control even at a normal hour, but at that time of night, it’s lawless. “How can I help you?”

“My daughter’s snake, Cutie, crawled into her dollhouse and got stuck.” The caller had a note of panic in her voice. “I can’t get her out.”

Well, at least this one’s still visible, I thought. Usually when a snake goes missing, it stays that way. Pet snakes love to disappear into the walls of our homes through cracks, holes, and pipes or under the floorboards. When that happens they’re almost never seen again. To a pet snake that spends his days and nights confined to a forty-gallon terrarium, wandering off is tempting once it gets out. Our homes hold the promise of freedom, of a grand adventure, except that the deeper they get into a labyrinth of hidden places, the more lost they get.

I’d first heard about a missing snake when I was working as a resident veterinarian at the Animal Medical Center in Manhattan.

“DID I TELL you I found my python?” my intern, Lauren, had asked me.

Lauren’s missing ball python, Cecil, had been the topic of much conversation in the surgery room. Ball pythons are a very popular pet snake, especially in apartments because they rarely grow longer than five or six feet and do not get very wide in girth—except they commonly go missing, often for months or even years at a time. I’d gone over to Lauren’s twenty-two-story high-rise in Midtown Manhattan, where many of the interns lived, to try to help find the brown-and-gold-speckled snake, but after a thorough search we conceded that he seemed to have disappeared without a trace. After several months, Lauren had given up on ever seeing him again.

“Where’d you find him?”

“Oh, I didn’t—another tenant did. My neighbor Jill got into the elevator, and there he was. Curled up in a tight little ball in the middle of the elevator floor. Pretty fantastic, right?”

Lauren was beaming, but I couldn’t help wondering if “fantastic” in this situation was a relative term. I doubted that Jill shared Lauren’s enthusiasm when she stepped into the elevator and found a four-foot python at her feet.

As if she’d heard my thoughts, Lauren chortled, “Well, I guess it did freak her out a little bit. She said she felt something touch her foot and ignored it until Cecil uncurled and started crawling up her leg. She screamed, kicked him off, and ran out of the elevator so fast, she said, that she left her strappy sandal behind.” Lauren giggled to herself. “Oh, Cecil, he doesn’t mean any harm.”

I imagined that Cecil must have survived for all those months on the building’s rodent population, but I didn’t share that conclusion with Lauren, since she still lived there. Stumbling upon a food source is the best-case scenario for a lost snake like Cecil, although snakes can survive for long periods without any food at all. They will curl up and go into a sort of shutdown mode, in which they slow their heartbeat, lower their temperature, and stop moving. Their already slow metabolism comes to a near standstill, and they can survive without food much longer than most any other animal I know of. I remembered my client Gus, the owner of a red, brown, and yellow milk snake that was about three inches in girth and went missing for nearly a year. Like Lauren, Gus had thought he’d never see his pet again, but the snake must have been living in the pipes behind his fridge. One morning, he slithered out of his hiding place, and Gus stumbled on him in the middle of the floor. Looking rather emaciated and weak, like a deflated bicycle tire, the snake was in desperate need of emergency care, so Gus gently coiled him up

and transported him to our hospital in the bottom of a laundry basket. There I treated him for extreme dehydration with a dose of an electrolyte solution under his skin and some liquid food through a tube passed down to his stomach.

I shook aside my memories of Cecil and Gus and calmly returned to the after-hours call. “How long has Cutie been in the dollhouse?”

“I guess . . . it’s been about two weeks now?”

I sat down and poured myself that glass of wine. I thought, Cutie’s been inside the dollhouse for more than two weeks, but right now, at eleven-thirty on a Saturday night, her owner has decided it’s finally time she move out.

“Does the snake appear to be hurt or in any pain?” I asked.

“Uh”—she paused again—“what would pain look like?”

“That’s a good question. It’s the difference between looking restful and frustrated. Does Cutie appear to be struggling, like she’s trying to get free?”

“Not really,” she replied. “She’s curled up in a ball in the master bedroom. I think she’s asleep.”

I took a sip of sauv blanc.

“And I’m sure she’s not hungry,” she continued. “I’ve been putting food on the front porch for her to eat.”

Just as I’d suspected, as with many of the distressed emergency calls I get from exotic pet owners late at night, Cutie did not need emergency care. She was already getting the best care right where she was. For two weeks she’d been checked into the best reptile bed-and-breakfast in town.

Her owner asked, “So what should I do?”

“Stop feeding her, and then on Monday, if Cutie still hasn’t checked out, call me back.”

7:15 A.M., VETERINARY CENTER

FOR BIRDS & EXOTICS

I LEFT THE ICU with Georgie’s chart and walked back to my office. I looked at the wall clock. We had just under an hour before the hospital opened to the crush of another busy Monday morning. I was going to need more coffee. I sank down in my Ikea desk chair and positioned myself in front of the phone. Veterinarians may joke that we become animal doctors so that we don’t have to deal with people, but that isn’t at all the case. Veterinary medicine is as much about building human relationships as about treating animals. When Maxine had brought her nearly lifeless glider into the hospital on Friday, I had seen immediately from the dark circles beneath her eyes that this distraught owner was going to need care and attention too.

Unlikely Companions

Unlikely Companions