- Home

- Laurie Hess

Unlikely Companions Page 8

Unlikely Companions Read online

Page 8

One evening, after picking up young Brett and baby Luke from a sitter’s down the street, I pulled up to our dark house. Scolding myself for having forgotten to turn on the porch lights, I unloaded the car and the boys in the darkness and fumbled to find the keyhole to open the door without loosening my hold on Luke. Once we finally got inside, I flipped on switch after switch, but we were still standing in darkness. Had we suffered a power outage? Had a fuse blown? After stumbling around in the dark with an infant on my hip and a whiney toddler trailing behind, I wondered if perhaps I’d forgotten to pay the electric bill. It sounded like the beginning of a great joke. What happens when a doctor and a lawyer don’t pay their electric bill? The same thing that happens to everyone who doesn’t pay: the lights go out.

I let out a series of G-rated expletives and then went searching for candles. If you could see the unspoken words between almost any husband and wife hanging in the air like in bubbles in a comic strip, they would read like this: “Why don’t you do something about this?” followed by “Why don’t you do something about this?” Feeling my way through the darkness, I found myself getting more and more resentful that Peter was not home to solve our problem. But by the next night, the lights were back on, and Peter and I were sharing an exhausted laugh over it as we lay collapsed together in a heap on the couch. The boys, the birds, and the cats were asleep. The house was quiet, and it was just us.

“I can just picture you”—Peter grinned—“trying to remain calm for Brett and Luke while cursing under your breath when you couldn’t find the emergency flashlight.”

“I never did find it. Thank goodness for Brett’s toy police car. We used the flashing siren to make our way upstairs.”

“I though you hated that toy.”

I did hate that toy. I had scolded my mom for giving it to Brett for his birthday. The siren was loud enough to wake the dead.

“Well, who knew it would actually come in handy?” I relented.

Peter took two sandwiches out of a paper bag and handed one to me. “Dinner?”

“At least it’s together,” I said with a smile. “Even if it’s just sandwiches.”

“Just sandwiches?” Peter took mock offense, unwrapping his pastrami. “Only from the best deli in Mount Kisco.” He took a bite. “Mmmm, these are almost as good as the sandwiches we used to get from the deli on Avenue B.”

“That good, huh?” I unwrapped my turkey club. Peter’s enthusiasm for the simple things in life is infectious. Deli sandwiches shared together on our living room couch suddenly felt as decadent as dining in Paris along the Seine. I leaned back against him. We were both so tired. Peter had dark hollows under his eyes, and I didn’t look much better. We gobbled our sandwiches in silence.

“I was thinking,” he finally said. “What if I made sure that the next time this happens, I’m here with you?”

I thought back to the night before, when I had wanted nothing more than for Peter to walk through the door and help me. I said, “There’s not going to be another time. I have all the bills set to autopay now. Even if I forget to pay them, the computer won’t.”

“Online banking. Wow, you’re really at the forefront of technology,” he teased. I turned and gave him a light punch on the shoulder.

“I mean it, though,” Peter said more seriously. “Situations like this are bound to keep coming up where you need me closer to home. What if I cut back my hours at the office?”

I tensed, and Peter could feel it.

“Let me guess,” he sighed. “You don’t like the idea.”

I took in a deep breath, but before I could respond Peter continued, “I know it wasn’t ‘the plan,’ but I want you to think about what we’re doing. We’re both killing ourselves nearly every day. I’m exhausted. You’re exhausted. It’s not good for our family, and”—he paused—“I worry about your health.”

Peter had a legitimate concern. Between work and running after two little boys, my health often slipped down the day’s priority list. I’d become less disciplined about exercising regularly and eating balanced meals, and unless I was making dinner for the family, I sometimes skipped eating altogether. If I were to be honest, it would be helpful to have Peter home more. But I feared it would come at a cost to my career.

I reminded Peter, “We agreed that you’d continue to work full-time at the firm while I worked to build up a loyal clientele of exotic pet owners in the area. I can’t open my own hospital without a solid list.”

“Yes, I know that was our agreement,” Peter said steadily, “but what if we both cut back, just a little bit?”

I crossed my arms and slowly shook my head. “No, I’m not willing to do that. I’m so close. I’ve worked so hard.”

Peter and I sat in silence for several minutes. Finally he said, “Laurie, I’ve always supported you, and I will never ask you to give up your dream. I’m simply suggesting that you put it on hold. I know you don’t want to hear this, but, honey, you just can’t do it all.”

No matter how right Peter was, I wasn’t ready to admit it.

I turned toward him and appealed, “Don’t cut back your hours yet. Give me a few more months to drum up clients. I can do it. Just a few more months at this pace, and then, I promise, we can both relax.”

Peter took a deep breath. He sat for a moment and then reluctantly agreed. The next morning, he caught the early train, as usual, into Manhattan; I dropped Brett at preschool and Luke at the sitter’s and left for the animal hospital in Rockland County where I worked one day a week. We didn’t resume our conversation again until nearly six months later when a nurse called him from the local hospital to tell him I’d passed out.

I was lying on an examination table, my eyelids as heavy as rocks, when I finally pushed them open. Peter was standing next to me with a bouquet of lavender tulips and a large Starbucks coffee. “This oughta wake you up,” he said, smiling. He was trying to be funny, but his eyes were worried and pinched. I knew he was scared. He sat down on the edge of the table.

“I spoke with your doctor.” His voice was serious now. “You collapsed from hypoglycemia and . . .” Peter paused as if he were holding something back.

“What?” I whimpered.

“Laurie”—he took my hand—“you’ve been diagnosed with adult-onset type 1 diabetes.” Peter squeezed my hand. “If you won’t listen to me, please, listen to your doctor. Listen to your body.”

I looked down at my thin outline tucked under a blanket, an IV stuck in my skinny arm. How long had I been out? How did I get here? Where were the boys?

Tears welled up in my eyes. Peter was right. I give.

“Okay,” I said quietly, “you’re right. I’ll stop. I can’t do it all.”

“You can do a lot.” Peter squeezed my hand. “Just not everything all at once.”

“I’ll take some time off,” I promised as tears ran down my cheeks. “But don’t get used to it,” I whimpered and then narrowed my eyes at him. “I’m not giving up on my career.”

“No.” Peter smiled and kissed me on the lips. “No doubt about that, Doctor. Plus, it won’t take long before the boys and I get tired of having you home so much.”

10:18 A.M., MAIN TREATMENT ROOM

AS I NIBBLED on my protein bar, I revisited the memory of that pivotal moment in my health, my career, and my marriage. So many of us get married and start new lives, not realizing that there will likely be hidden costs we hadn’t envisioned—compromises we’ll have to make, dreams, pastimes, habits we’ll be asked to leave behind in order to forge a new path ahead with our spouse or partner. When I conceded that I would have to put my career on hold in order to take care of my health and my family, I feared I was giving up my professional dream, choosing one love over another. But looking back now, I realized that wasn’t true. I had just postponed the opening of the animal hospital for a few years. The timing of my plans shifted, but Peter had never actually asked me to give anything up. And I hadn’t.

Bob Dixon, I now und

erstood, had similarly tried to make compromises to maintain the peace in his marriage over the years. But now his treasured sugar gliders were sick and quite possibly dying, and it appeared that he still felt he had to keep their treatment a secret from his wife. Or what? I wondered. Would she deny treatment, as Susan Mitchell had feared her husband would do when he learned about her guinea pig Rosie’s dire condition?

I looked down into Lily and Mathilda’s cage. The younger glider had reduced herself to a small lump, and her lids were drawn tautly over her eyes. Lily was protectively snuggled up next to her.

Marnie walked up behind me. I shook my head and said, “It’s happening all over again. Her system is beginning to shut down.”

If Mathilda was on the same trajectory and timetable as Georgie, she would die in a matter of days.

“I have to call Bob.”

I stepped outside the main treatment room and dialed his number from my private cell phone. He answered on the first ring.

“It’s Dr. Hess,” I said, “and I know you don’t want me to call you directly, but it couldn’t wait. It’s Mathilda. I need you to come in right away.”

As I waited for Bob to drive the thirty minutes it would take him to arrive at the hospital, I determined that I had time to meet with one more patient. A very special patient: Bennie Weston and his chinchillas. Bennie would be a welcome reprieve on a day when grim news was becoming the theme.

I swung open the door of examination room number two. “Hi, Bennie!”

A heavyset, middle-aged man looked down at the ground and softly muttered a hello. His elderly mother, Sheila, and I exchanged a delighted smile. After all, less than a year ago, Bennie’s mother had still been doing all the talking for him.

“How are the guys?” I knelt down in front of a cage housing three fuzzy gray-and-black chinchillas. Bennie had adopted the trio from a nearby shelter when they were babies.

“Their names are Gigabyte, Megabyte, and Mac,” Bennie said matter-of-factly. “Don’t you remember?”

“Yes, of course, I remember,” I said with a smile. “How could I forget?”

Although Bennie was highly functioning when it came to caring for his pets, socially he could be as nervous and withdrawn as a chinchilla. Sheila once explained out of earshot of her son, “It’s like Bennie was born into a world where everyone has the owner’s manual but him. He tries very hard to fit in, but it’s difficult. Those animals love him though,” she said tenderly. “For whatever reason, he’s able to connect with those funny little fur balls in a way that he can’t do with the rest of us.”

I understood that Gigabyte, Megabyte, and Mac were able to reach that place inside Bennie that was closed and inaccessible to all others, including his mother. I watched as Bennie spoke in a soft and intimate way to his three animals in their cage. I’d see this sort of special connection to animals before among other children and socially awkward adults. I’d witnessed in the hospital what many studies have also shown—that such people can relax, communicate, and interact with their pets, when they can’t easily do the same with people.

Bennie really wasn’t that different from anyone else. We all crave that special friend whom we can connect with, whether it’s a chinchilla, a sugar glider, or a pionus parrot. Bennie had found his, and today Bennie’s three companions were huddled so shyly in the corner of their carrier that I could hardly pry them out.

“Let me,” Bennie said. As he pulled them out, one by one, their bodies relaxed as they recognized Bennie’s hands and gentle voice.

“It’s okay, friends,” he assured them. “Doctor Hess just wants to examine you.” He slowly handed me his chinchillas, one at a time, and I held each close to my body as I examined them, head to tail, paying careful attention to their teeth. I always make it a priority to thoroughly examine a chinchilla’s mouth. These small rodents are known for developing dental problems because their teeth continue to grow throughout their lifetimes, and the incisors’ roots are particularly long. Chinchillas consume rough grasses and shrubs in the wild, which helps wear down their teeth naturally so that they stay healthy. But captive chinchillas are often fed only pellets, so their teeth can become overgrown and easily become impacted.

“I think Mac is eating more than the others,” Bennie said. Then he paused as if he were carefully formulating his next thought. “I weighed him this morning, and he’s over the appropriate level.”

Bennie made a habit of weighing his chinchillas every morning and carefully measured their food. This wasn’t necessary—the rodents weren’t on the Weight Watchers plan—but the daily ritual made Bennie feel more in control of his environment.

“I bet he’s just fine, Bennie, but let’s weigh him on my scale just to be sure.” Sheila nodded at her son, legitimizing his concerns, and Bennie walked over and placed Mac on the scale, intently watching the reading.

“See there. One and a half pounds,” I said. “Mac seems to be at the correct weight, but remember when we discussed digestion and how weight fluctuates during the day? Depending on what time Mac eats, his weight will change a little.”

Bennie nodded that he understood.

“Everything looks just as it should. You’re doing a fantastic job,” I said.

“I’m doing a fantastic job,” Bennie repeated quietly under his breath.

Marnie poked her head into the examination room. “Hi, Bennie. Hi, Mrs. Weston. Sorry to interrupt, but when you’re finished, Laurie, Bob is here.”

Bennie perked up. “Can I go see Colette now?”

Sheila and I exchanged delighted looks.

“Bennie makes his own appointments now,” Sheila said proudly.

Mrs. Weston slowly lifted herself up out of her chair. I noticed her putting her hands on her knees and hesitating for a moment before she pushed herself up to a standing position. She reached for the cage, but Bennie stepped in front of her.

“No, Mom. I will get it.” He picked up the cage and then opened the examination door for his mother.

“Thank you, son.” She patted his arm and slowly stepped forward.

Not so long ago, Bennie wouldn’t have noticed that his mother needed help, not because he didn’t care for her but because other people’s needs weren’t on his radar. I had no doubt that Bennie’s expression of empathy now was the direct result of learning to tend to Gigabyte, Megabyte, and Mac.

I joined Marnie in the main treatment room, where Bob was hunched over Lily and Mathilda’s cage. He straightened up when he heard me enter.

“Thank you for getting here so fast,” I said. “I didn’t think it could wait.”

“I’ve explained Mathilda’s progressive paralysis and weakness to Bob,” Marnie said, “but I think he has a few more questions.”

“I don’t understand,” Bob said helplessly. “Why is this happening to her?”

My heart ached. Maxine had asked me the same thing.

“There’s something you should know,” I said gently.

Bob looked anxiously from me to Marnie. “What is it?”

“Mathilda is exhibiting equivalent symptoms to four other sugar gliders I’ve recently treated at the hospital.” I paused and looked at Marnie, who gave me an encouraging nod. “I regret to say that so far, not one of them has survived.”

The color drained out of Bob’s face.

1:00 P.M., MY OFFICE

THE DAY WAS hardly halfway over, and I just wanted to pack up, go home to my family, and take some downtime to think. I’d spent over an hour with Bob, recounting everything I knew and was still investigating about the unexplained sugar glider deaths. As expected, he was alarmed by how quickly the sickness was spreading, and he was frightened for Lily and Mathilda. I’d assured him I was doing everything in my power to determine the cause of the sickness before it took another life. Whereas someone else might have condemned me for my inadequacy and what was beginning to feel like failure, Bob had simply said, “I trust you. Do whatever you can.” This is perhaps the biggest compli

ment a veterinarian can get from a pet owner, and Bob’s faith in me created an even greater sense of urgency. What else could I do to help this man and his gliders?

As I slumped down in my office chair and nervously ran a hand through my hair, I noticed the message light blinking on my office phone. I felt a surge of both anticipation and apprehension. I reached out and pressed play.

“Hello, Dr. Hess.” I recognized the voice immediately. It was Mr. Huntington. “My granddaughter’s sugar glider, Pockets, recently passed away at your hospital. You said in your voice mail that you wanted to know where Pockets came from.”

I leaned forward and held my breath.

“I bought him at the Johnson Valley Mall.”

3

A CONNECTION

WEDNESDAY, 7:15 A.M., HOME

First thing the next morning, I dumped a cup of cat food into the cat feeder in my kitchen. Gizmo, Tilly, Bean, and Bingo threaded themselves through my legs.

“How did I end up with so many cats?” I muttered aloud to myself.

Of course, I knew the answer. They’d entered the house in stages. We’d adopted Bean, the friendliest and also the most senseless cat, from the SPCA. He’d chased his own shadow for nearly a year until I went looking to find him a buddy. I found two—Bingo and Gizmo, both huge and feral. I’d seen a listing in the local Penny Saver from a woman in upstate New York. I answered the ad, and she invited me to her house where I met over a dozen strays living in her small laundry room. I singled out Bingo, who seemed the most docile, but his hissing and spitting brother Gizmo wouldn’t let me near him.

“Looks like you’ll have to take them both,” said the owner of the animals. “Keep the siblings together, right?”

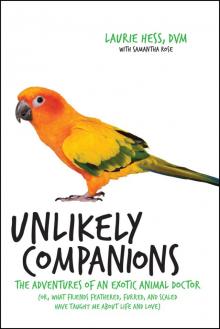

Unlikely Companions

Unlikely Companions